As you enter Lothbury Court (hauling a load of bullion in a cart behind you no doubt) impressive flights of steps rise on both sides, but straight ahead ... a triumphal arch in the Roman manner. It's almost a month since I set to work on this.

It was already roughed out, but needed to be lifted to the next level of development. There are four statues atop of four Corinthian columns. I don't know if there's a proper term for the way the entablature is projected over the columns in a series of spurs that act as bases for the statues. And I don't know who the four mythical creatures are. I'm sure they have signigicance. For now I am simply using the grecian maiden who serves as a caryatid in a couple of the transfer halls. That's the only mesh I have which is remotely suitable, so it will have to do.

The central panel at this level is a key pattern. We only have a very grainy image to base this on, so I blew it up and traced over the image freehand on my phone. That gave me something that was crisp enough when loaded into Revit to trace over without getting totally lost. Started with a filled region, and copy-pasted the sketch footprint into an extrusion in Family Editor..

It amazes me how many variations you can invent, based on these "standard" classical devices. Turns out that the standard is pretty flexible. Maybe the BIM world can learn something from this ? One day I will count up how many different key patterns Soane used in the Bank, double figures for sure. I reused an existing face based family for a recessed panel, copied my extrusion of the basic module and adapted it at the ends and the middle to complete the design.

Next I needed another classical device, Caduceus: the staff of Hermes. It's a symbol of commerce (two snakes for commerce, one for medicine ... I think ?) I had made a version for the dividend office (colonial?) sitting in the pendentives of the dome. While pilfering this, I decided to "give back" my improved caryatid. Last time I touched this area was a couple of years ago, before I learnt how to hide the edges in a CAD mesh. So the caryatids were represented rather crudely by a stack of 3 or 4 blends.

So on we go, adding more panels. Hanging garlands at the sides. Leaves and ribbons, carved in stone, represented in digital 3d by simple extrusions! But it works, just about. I adapted the blind windows from the Lothbury Screen Wall, among the earliest families to be made for Project Soane and I can't remember who started them off. I know I have updated them two or three times.

It suddenly strikes me that the pairing of Residence Court and lothbury court is a bit like a church. The Nave is represented by Residence Court looking towards the apse which is towards the East as it should be) The rows of free-standing columns stand in for the timber choir screens you often see in old cathedrals, and the bullion route provides the crossing. I wonder if this metaphor ever occured to Soane.

Much more detail could be added. Rows of dentils around the cornice for example. For the moment I contented myself with pilasters to frame the apse, plus horizontal mouldings and a proper door in the middle.

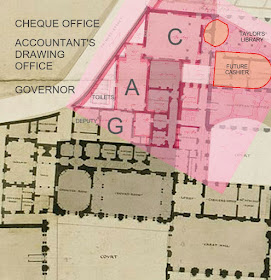

Then I move on to the roofs either side of the bullion tunnel and the top floor rooms around the Bullion Court. What fascinating irregular worlds Soane's roofs are, hiding behind the classical regularity of his elevations. I love the way that the two half-domes jostle either side of the tunnel (the Chief Cashier's Office & the Power of Attorney Office (PoA) But I'm not sure how to develop the interior of the PoA. It's a semicircular space with a circulation route along the flat side and needs to be top lit, so the lunette window seems right, but that long plain opening below is puzzling.

That was an excellent weekend. I loaded up all the links and pubished a new version of the model to A360. Russell's Consols Transfer Office, and Alberto's Stock Office sitting proudly with their grey roofs, top centre. I haven't quite reached the level of detail that they achieved in the rest of the model yet, but it's coming closer.

I'm not quite happy with the roofs over the residence court yet. Nothing much to go on there, I will have to make something up eventually. Maybe they were just flat as I show them now, but other areas that used to be shown as flat expanses have developed so magnificently ... ideas are welcome. But all in all, I'm feeling very positive. Who knows, I may even "finish" this project one day.

It was already roughed out, but needed to be lifted to the next level of development. There are four statues atop of four Corinthian columns. I don't know if there's a proper term for the way the entablature is projected over the columns in a series of spurs that act as bases for the statues. And I don't know who the four mythical creatures are. I'm sure they have signigicance. For now I am simply using the grecian maiden who serves as a caryatid in a couple of the transfer halls. That's the only mesh I have which is remotely suitable, so it will have to do.

The central panel at this level is a key pattern. We only have a very grainy image to base this on, so I blew it up and traced over the image freehand on my phone. That gave me something that was crisp enough when loaded into Revit to trace over without getting totally lost. Started with a filled region, and copy-pasted the sketch footprint into an extrusion in Family Editor..

It amazes me how many variations you can invent, based on these "standard" classical devices. Turns out that the standard is pretty flexible. Maybe the BIM world can learn something from this ? One day I will count up how many different key patterns Soane used in the Bank, double figures for sure. I reused an existing face based family for a recessed panel, copied my extrusion of the basic module and adapted it at the ends and the middle to complete the design.

Next I needed another classical device, Caduceus: the staff of Hermes. It's a symbol of commerce (two snakes for commerce, one for medicine ... I think ?) I had made a version for the dividend office (colonial?) sitting in the pendentives of the dome. While pilfering this, I decided to "give back" my improved caryatid. Last time I touched this area was a couple of years ago, before I learnt how to hide the edges in a CAD mesh. So the caryatids were represented rather crudely by a stack of 3 or 4 blends.

So on we go, adding more panels. Hanging garlands at the sides. Leaves and ribbons, carved in stone, represented in digital 3d by simple extrusions! But it works, just about. I adapted the blind windows from the Lothbury Screen Wall, among the earliest families to be made for Project Soane and I can't remember who started them off. I know I have updated them two or three times.

It suddenly strikes me that the pairing of Residence Court and lothbury court is a bit like a church. The Nave is represented by Residence Court looking towards the apse which is towards the East as it should be) The rows of free-standing columns stand in for the timber choir screens you often see in old cathedrals, and the bullion route provides the crossing. I wonder if this metaphor ever occured to Soane.

Much more detail could be added. Rows of dentils around the cornice for example. For the moment I contented myself with pilasters to frame the apse, plus horizontal mouldings and a proper door in the middle.

Then I move on to the roofs either side of the bullion tunnel and the top floor rooms around the Bullion Court. What fascinating irregular worlds Soane's roofs are, hiding behind the classical regularity of his elevations. I love the way that the two half-domes jostle either side of the tunnel (the Chief Cashier's Office & the Power of Attorney Office (PoA) But I'm not sure how to develop the interior of the PoA. It's a semicircular space with a circulation route along the flat side and needs to be top lit, so the lunette window seems right, but that long plain opening below is puzzling.

That was an excellent weekend. I loaded up all the links and pubished a new version of the model to A360. Russell's Consols Transfer Office, and Alberto's Stock Office sitting proudly with their grey roofs, top centre. I haven't quite reached the level of detail that they achieved in the rest of the model yet, but it's coming closer.

I'm not quite happy with the roofs over the residence court yet. Nothing much to go on there, I will have to make something up eventually. Maybe they were just flat as I show them now, but other areas that used to be shown as flat expanses have developed so magnificently ... ideas are welcome. But all in all, I'm feeling very positive. Who knows, I may even "finish" this project one day.