We are continuing where we left off last time. Six London churches from the early 1700s, all designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor using his very personal vision of the English Baroque. We started in Greenwich and have been moving inland. Last stop was Limehouse.

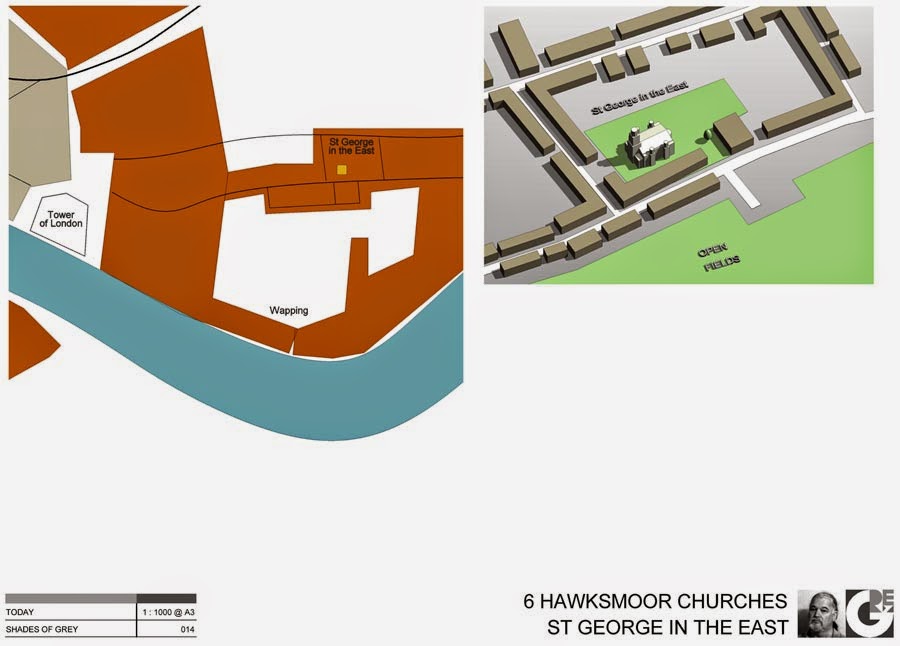

Moving further west we arrive at Shadwell & Wapping. Around 1720 there would have been wharves & warehouses all along the river front, with open ground behind, some of it devoted to gardens. A little further inland was the main road heading towards Limehouse (Ratcliff Highway) which hosted a ribbon of residential development. Here Hawksmoor built St George in the East.

The site was the interior of a large residential block, with houses backing on to it most of the way around. Some of this housing was flattened during the blitz and the south side has been left open. Once again the site pushes the orientation slight off an ideal E/W alignment and the circulation strategy changes once again.

This time we have four entrances at the four corners of the main mass. The vertical circulation is by spiral stairs placed just inboard of these entrances and expressed as towers with pepper pot domes aloft. These stairs also have doors at ground level, so that galleries and nave seating have separate but interconnected circulation routes.

Was Hawksmoor dissatisfied with his previous circulation schemes, and looking for ways to get people in and out of the building more fluently ? Or is he just playing games, ringing the changes ?

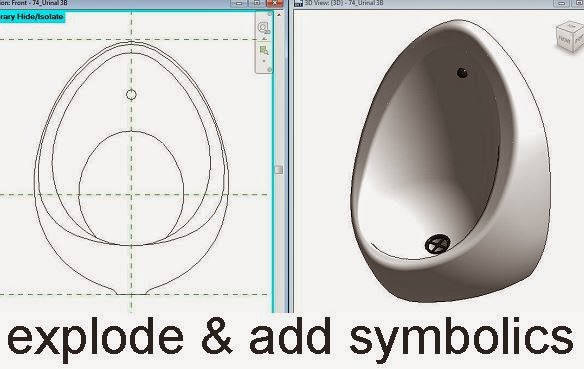

By now I am developing a version of the massing model that stands up to closer inspection. Not yet ready to switch to project mode, but I do want my family to support a more detailed study of the building's composition. For plan views at a finer scale I am using an embedded detail component. Not BIM, do you say ? I beg to differ. For urban design studies this is an entirely appropriate lightweight method for representing signature buildings within a broader scheme.

The tower is a compromise between the two previous schemes: partially separated from the building but still supported with side buttressing. In the next image you can also see the detailed model side by side with the simpler version.

If St George is due East from the City, Spitalfields is North East, and slightly closer in. This is a suburb based on textiles, which were the mainstay of the English economy right through the middle ages and into the first half of the Industrial Revolution.

Once again we touch upon the antagonism between Catholic/Absolutist France and Protestant/Parliamentary England. Spitalfields was home to thousands of Huguenot silk weavers: refugees fleeing from sectarian violence (sound familiar?) France's loss was England's gain. Traditionally England had specialised in coarser textiles: wool and linen. The Spitalfields weavers added a finer product to the portfolio, often decorated with fancy needlework: a luxury product.

The site is different once again: a corner plot diagonally opposite a large open market square that was covered over in the nineteenth century and still flourishes today. It has to be a long thin church and luckily the west end is towards the square, so nice opportunity for a grand entrance frontage. But was it luck ? Were the sites predetermined or could Hawksmoor/and or the commission negotiate. I've no idea, let's stick with the notion that the buildings were designed to suit a given site.

This time there are no galleries. The church is very directional, rows of columns striding down the nave. There are 2 doors tucked away at the back corners, but the main circulation routes are clearly at the front end: 3 doors entered via a grand portico.

To my eyes, the tower and portico are decidedly odd: something about the proportions perhaps. Once again there are side buttresses to the tower. I get the impression that they started as pillars like St George, then got wider to allow for a grand portico and created an opportunity for a concave, linking sweep. To crown it all is a pyramid, which ends up being more of a gothic spire.

Moving further west we arrive at Shadwell & Wapping. Around 1720 there would have been wharves & warehouses all along the river front, with open ground behind, some of it devoted to gardens. A little further inland was the main road heading towards Limehouse (Ratcliff Highway) which hosted a ribbon of residential development. Here Hawksmoor built St George in the East.

The site was the interior of a large residential block, with houses backing on to it most of the way around. Some of this housing was flattened during the blitz and the south side has been left open. Once again the site pushes the orientation slight off an ideal E/W alignment and the circulation strategy changes once again.

This time we have four entrances at the four corners of the main mass. The vertical circulation is by spiral stairs placed just inboard of these entrances and expressed as towers with pepper pot domes aloft. These stairs also have doors at ground level, so that galleries and nave seating have separate but interconnected circulation routes.

Was Hawksmoor dissatisfied with his previous circulation schemes, and looking for ways to get people in and out of the building more fluently ? Or is he just playing games, ringing the changes ?

By now I am developing a version of the massing model that stands up to closer inspection. Not yet ready to switch to project mode, but I do want my family to support a more detailed study of the building's composition. For plan views at a finer scale I am using an embedded detail component. Not BIM, do you say ? I beg to differ. For urban design studies this is an entirely appropriate lightweight method for representing signature buildings within a broader scheme.

The tower is a compromise between the two previous schemes: partially separated from the building but still supported with side buttressing. In the next image you can also see the detailed model side by side with the simpler version.

If St George is due East from the City, Spitalfields is North East, and slightly closer in. This is a suburb based on textiles, which were the mainstay of the English economy right through the middle ages and into the first half of the Industrial Revolution.

Once again we touch upon the antagonism between Catholic/Absolutist France and Protestant/Parliamentary England. Spitalfields was home to thousands of Huguenot silk weavers: refugees fleeing from sectarian violence (sound familiar?) France's loss was England's gain. Traditionally England had specialised in coarser textiles: wool and linen. The Spitalfields weavers added a finer product to the portfolio, often decorated with fancy needlework: a luxury product.

The site is different once again: a corner plot diagonally opposite a large open market square that was covered over in the nineteenth century and still flourishes today. It has to be a long thin church and luckily the west end is towards the square, so nice opportunity for a grand entrance frontage. But was it luck ? Were the sites predetermined or could Hawksmoor/and or the commission negotiate. I've no idea, let's stick with the notion that the buildings were designed to suit a given site.

This time there are no galleries. The church is very directional, rows of columns striding down the nave. There are 2 doors tucked away at the back corners, but the main circulation routes are clearly at the front end: 3 doors entered via a grand portico.

To my eyes, the tower and portico are decidedly odd: something about the proportions perhaps. Once again there are side buttresses to the tower. I get the impression that they started as pillars like St George, then got wider to allow for a grand portico and created an opportunity for a concave, linking sweep. To crown it all is a pyramid, which ends up being more of a gothic spire.