I think it's fair to say that churches are very prominent in the history of Western Architecture. Clearly they are deeply loaded with symbolic meaning. I was brought up a Christian, but the "plain meeting room" kind, and I've been an atheist for at least 45 years now, so what meaning would I find in a church building? Why would I set about modeling and analysing a church?

I can look at the technology, materials & structural forces. We could think about response to climate (I guess, although that aspect is probably less relevant that in a dwelling) and of course we can look at aesthetics in a fairly abstract way (rhythm, proportions, symmetry) but without meaning it all falls a bit flat. Music is much more interesting when it evokes an emotional response.

I carried out a series of studies of Hawksmoor's London churches some years ago, but that was handled at the Urban Design level and strongly influenced by my excitement about rediscovering the city that I first fell in love with as a student ... 45 years ago (again) More recently I modelled on of John Soane's three London churches. Here the motivation was to take on a Soane building that I might actually be able to finish (lol) and to compare different aspects of his style and design approach.

https://grevity.blogspot.ae/2014/11/six-of-best.html

https://grevity.blogspot.ae/2014/11/more-hawksmoor-churches.html

https://grevity.blogspot.ae/2014/12/wool-gathering.html

I've been modelling the church of San Giusto Nuovo in Volterra. This time it was about doing something tangible with the point cloud and photogrammetry information that we acquired during the workshop I recently attended. But of course, the more churches you model, the more you start to aske questions and make questions and as a human being it's pretty much impossible to avoid looking for "meaning".

This is the first time I have used a point cloud to inform my modeling. It's been a wonderful experience, not perfect, but so much better than fumbling around with the kind of source material I usually start from.

One little trick that I developed to combat the sluggish response when trying to model on top of a point cloud. Let's say you are in an elevation or section view and you want to model a particular decorative element. Take a reference dimension based on points that you have already established, then use the snipping tool to save a jpeg of the area in question. Switch over to family editor using a suitable template. Paste in the jpeg (I wish you could just paste into Revit from the clipboard) and scale it based on the reference dimension. Now you can trace over the reference image without Revit trying to snap to individual points within the scan data, or struggle to regenerate the screen as you zoom in and out.

San Giusto appears to be the Italian version of Saint Justus, a fairly common name. "James the just" comes to mind, "just" to prove that I have a residual biblical memory, and via this sentence, that words "speciate" into multiple branches of meaning, simply by being used. "Ius" was a Latin word for legal right, it came to mean correct, or precise and you can perhaps see how that slipped sideways into "only". "Just So" stories started off meaning exactly so, but by being applied to rather fanciful tales flipped its meaning so that "Justice" became "Fake News". Which I suppose is poetic justice. Words are slippery.

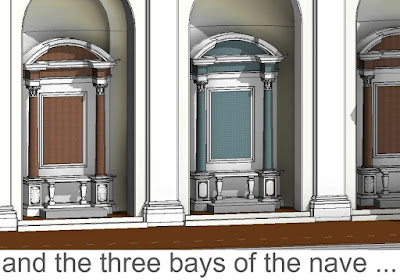

There are smaller scrolls to terminate buttress walls down the sides of the building. These line up with the internal arches that divide the nave into three bays, before the crossing. Once again the point cloud was a wonderful tool for fine tuning the size and shape, but less so for articulating the form itself. The yellow stone used here is quite soft, so there's a good deal of erosion and patching up. Captured Reality can be quite irregular. I choose to model an idealised version of the church. Purified or justified perhaps.

So the aim is to capture the design intent, to evoke a scroll in you mind's eye. The size and proportions will be very close, but in Revit the ramped end of the spiral is always going to be a bit of a nightmare. So I will cheat. The starting point is an extrusion, drawn in a side view and adjusted to match the scan. Then I add sweeps, picking the edges of the extrusion for my path and using a profile a bit like a turned baluster.

I wasn't able to do this "all in one" so I split it into three sections which proved useful later on. I've done something similar before with the Ionic capital. You can add two cylinders then extend the edge curves so they disappear almost tangentially into the sides of those cylinders. The result is quite convincing and your brain does the rest.

One of my goals for the workshop was to use photogrammetry to capture sculptural detail and embed this into a Revit family. Recap photo was struggling a bit on site, probably down to the flaky internet, but Dave Dreffs took some of my efforts and converted them successfully. Here are some of the source photos. It's a coat of arms taken from the plinth of one of the side altars that line the nave of the church. I am assuming this has to do with local patrician families displaying their piety/investing in the afterlife.

Recap photo stitches these up automatically and spits out a textured mesh. It can be quite detailed and quite heavy. In this case an obj file of around 100mb. Dave also made a nice little video clip, which I think you can do in Recap Photo itself. I've been a bit lazy about spending time in these apps to be honest. Or to put it another way ... impatient to use the results within Revit and get on with analysing the building.

https://youtu.be/HGhXZdvzwJA

3d Studio Max will open the obj file. I am a total novice here, but you can then go to Modifiers/Mesh Editing/Pro Optimiser. This will allow you to decimate the mesh, basically reduce the face count. You can also do this in Recap Photo, but you are going to use Max to convert to DXF anyway. You need to be pretty drastic. The DXF version we are using (2004) has a limit of about 32k vertices.

Next step, is a process I have described before where you can select all the edges and make them invisible. If you don't do this the mesh is going to look really awful in Revit. To put it another way, by hiding the edges in this mesh you can have edges switched on for normal Revit geometry without this shield turning into a black blob because of the thousands of visible edges. Another workaround is to set the line colour for the mesh to a pale grey, but this is a poor second best.

https://grevity.blogspot.ae/2016/03/be-gone-sharp-edges.html

https://grevity.blogspot.ae/2017/07/kak-handed.html

Here is my mesh brought into the altar family. The black edges really help to define the mouldings around the plinth, but the lack of edges within the coat of arms disguises the fact that is is actually a mesh of tiny little triangles. Revit does actually create the occasional black edge where the geometry is strongly undercut, but this is a bit unpredictable and changes as you rotate the view angle.

Ultimately I made the coat of arms as a nested family and created another one that can be swapped out with a type parameter. This is just a simple lozenge shape which is based on the reality at San Giusto. Perhaps some of the entities sponsoring the altars didn't have a coat of arms, or maybe they were taking the economy route.

To get the coat of arms to show up nicely in a hidden line section view, you will need to add some symbolic lines. The whole process is quite time consuming. Minimum of twenty photos from different angles, process them all in Recap Photo, decimate the mesh, hide the edges and convert to dxf, embed in a family (scale to suit) set the material in object styles, add symbolic lines/masking regions to taste.

But if you want to model historic buildings like this in Revit it does add a layer of reality that is difficult to achieve any other way. We've already talked about fooling the eye/brain. To be honest, all drawing/modelling/artistic representation comes down to this. Whether you are Michelangelo, or Marvel Comics ... you are using sleight of hand to trigger the brain's pattern recognition system into believing a "just-so" story. Of course, Enscape helps

In the end you want to do "just enough" to convey the message you intend. In this case it is a question of finding a balance between abstraction and reality that will allow us to ask useful questions about the building: how it is built, what it meant to the community that used it, how does it compare to say St Peter, Walworth built by John Soane a century or so later. My initial interpretation of the bays was that the arches extended into cross-walls carrying beams that run lengthways along the nave. But I think the span is too large and the continuity of the roof void impeded. Who knows? It would be wonderful to venture up into that space.

So I have reverted to a trusses above "shell vaults" interpretation. We did see lots of examples of ceiling vaults built with the shallow flat bricks that predominate locally. Again, I would love to see Tuscan tradesmen constructing these vaults. One of the advantages of building a model from scratch with software like Revit is that you can create it "as it used to be". Whereas a point cloud just captures a moment in time with whatever alterations and clutter have accumulated over time. So I restored the high level windows along the aisle, on the assumption that they used to exist. Another open question, and there are many more to be asked.

So that is my version of San Giusto, Volterra as it stands today. I would love to explore some deeper questions. I haven't mentioned the question of the bell tower which seems to rest partly on the edge of a vault, nor the fact that I have omitted the lean-to structures either side of the "east end". These look to be later additions, but they could be altered versions of rooms that were there originally. The church was designed in 1628 though for some reason not consecrated until 1775. The style puzzles me a little. It is often described as Neoclassical or Renaissance, which I take to be generic terms. The date would put it in the Baroque period and it does strike me as a kind of very simple, "rustic" version of Baroque. But those are discussions for another day. Much to be done.

I can look at the technology, materials & structural forces. We could think about response to climate (I guess, although that aspect is probably less relevant that in a dwelling) and of course we can look at aesthetics in a fairly abstract way (rhythm, proportions, symmetry) but without meaning it all falls a bit flat. Music is much more interesting when it evokes an emotional response.

I carried out a series of studies of Hawksmoor's London churches some years ago, but that was handled at the Urban Design level and strongly influenced by my excitement about rediscovering the city that I first fell in love with as a student ... 45 years ago (again) More recently I modelled on of John Soane's three London churches. Here the motivation was to take on a Soane building that I might actually be able to finish (lol) and to compare different aspects of his style and design approach.

https://grevity.blogspot.ae/2014/11/six-of-best.html

https://grevity.blogspot.ae/2014/11/more-hawksmoor-churches.html

https://grevity.blogspot.ae/2014/12/wool-gathering.html

I've been modelling the church of San Giusto Nuovo in Volterra. This time it was about doing something tangible with the point cloud and photogrammetry information that we acquired during the workshop I recently attended. But of course, the more churches you model, the more you start to aske questions and make questions and as a human being it's pretty much impossible to avoid looking for "meaning".

This is the first time I have used a point cloud to inform my modeling. It's been a wonderful experience, not perfect, but so much better than fumbling around with the kind of source material I usually start from.

One little trick that I developed to combat the sluggish response when trying to model on top of a point cloud. Let's say you are in an elevation or section view and you want to model a particular decorative element. Take a reference dimension based on points that you have already established, then use the snipping tool to save a jpeg of the area in question. Switch over to family editor using a suitable template. Paste in the jpeg (I wish you could just paste into Revit from the clipboard) and scale it based on the reference dimension. Now you can trace over the reference image without Revit trying to snap to individual points within the scan data, or struggle to regenerate the screen as you zoom in and out.

San Giusto appears to be the Italian version of Saint Justus, a fairly common name. "James the just" comes to mind, "just" to prove that I have a residual biblical memory, and via this sentence, that words "speciate" into multiple branches of meaning, simply by being used. "Ius" was a Latin word for legal right, it came to mean correct, or precise and you can perhaps see how that slipped sideways into "only". "Just So" stories started off meaning exactly so, but by being applied to rather fanciful tales flipped its meaning so that "Justice" became "Fake News". Which I suppose is poetic justice. Words are slippery.

There are smaller scrolls to terminate buttress walls down the sides of the building. These line up with the internal arches that divide the nave into three bays, before the crossing. Once again the point cloud was a wonderful tool for fine tuning the size and shape, but less so for articulating the form itself. The yellow stone used here is quite soft, so there's a good deal of erosion and patching up. Captured Reality can be quite irregular. I choose to model an idealised version of the church. Purified or justified perhaps.

So the aim is to capture the design intent, to evoke a scroll in you mind's eye. The size and proportions will be very close, but in Revit the ramped end of the spiral is always going to be a bit of a nightmare. So I will cheat. The starting point is an extrusion, drawn in a side view and adjusted to match the scan. Then I add sweeps, picking the edges of the extrusion for my path and using a profile a bit like a turned baluster.

I wasn't able to do this "all in one" so I split it into three sections which proved useful later on. I've done something similar before with the Ionic capital. You can add two cylinders then extend the edge curves so they disappear almost tangentially into the sides of those cylinders. The result is quite convincing and your brain does the rest.

One of my goals for the workshop was to use photogrammetry to capture sculptural detail and embed this into a Revit family. Recap photo was struggling a bit on site, probably down to the flaky internet, but Dave Dreffs took some of my efforts and converted them successfully. Here are some of the source photos. It's a coat of arms taken from the plinth of one of the side altars that line the nave of the church. I am assuming this has to do with local patrician families displaying their piety/investing in the afterlife.

Recap photo stitches these up automatically and spits out a textured mesh. It can be quite detailed and quite heavy. In this case an obj file of around 100mb. Dave also made a nice little video clip, which I think you can do in Recap Photo itself. I've been a bit lazy about spending time in these apps to be honest. Or to put it another way ... impatient to use the results within Revit and get on with analysing the building.

https://youtu.be/HGhXZdvzwJA

3d Studio Max will open the obj file. I am a total novice here, but you can then go to Modifiers/Mesh Editing/Pro Optimiser. This will allow you to decimate the mesh, basically reduce the face count. You can also do this in Recap Photo, but you are going to use Max to convert to DXF anyway. You need to be pretty drastic. The DXF version we are using (2004) has a limit of about 32k vertices.

Next step, is a process I have described before where you can select all the edges and make them invisible. If you don't do this the mesh is going to look really awful in Revit. To put it another way, by hiding the edges in this mesh you can have edges switched on for normal Revit geometry without this shield turning into a black blob because of the thousands of visible edges. Another workaround is to set the line colour for the mesh to a pale grey, but this is a poor second best.

https://grevity.blogspot.ae/2016/03/be-gone-sharp-edges.html

https://grevity.blogspot.ae/2017/07/kak-handed.html

Here is my mesh brought into the altar family. The black edges really help to define the mouldings around the plinth, but the lack of edges within the coat of arms disguises the fact that is is actually a mesh of tiny little triangles. Revit does actually create the occasional black edge where the geometry is strongly undercut, but this is a bit unpredictable and changes as you rotate the view angle.

Ultimately I made the coat of arms as a nested family and created another one that can be swapped out with a type parameter. This is just a simple lozenge shape which is based on the reality at San Giusto. Perhaps some of the entities sponsoring the altars didn't have a coat of arms, or maybe they were taking the economy route.

To get the coat of arms to show up nicely in a hidden line section view, you will need to add some symbolic lines. The whole process is quite time consuming. Minimum of twenty photos from different angles, process them all in Recap Photo, decimate the mesh, hide the edges and convert to dxf, embed in a family (scale to suit) set the material in object styles, add symbolic lines/masking regions to taste.

But if you want to model historic buildings like this in Revit it does add a layer of reality that is difficult to achieve any other way. We've already talked about fooling the eye/brain. To be honest, all drawing/modelling/artistic representation comes down to this. Whether you are Michelangelo, or Marvel Comics ... you are using sleight of hand to trigger the brain's pattern recognition system into believing a "just-so" story. Of course, Enscape helps

In the end you want to do "just enough" to convey the message you intend. In this case it is a question of finding a balance between abstraction and reality that will allow us to ask useful questions about the building: how it is built, what it meant to the community that used it, how does it compare to say St Peter, Walworth built by John Soane a century or so later. My initial interpretation of the bays was that the arches extended into cross-walls carrying beams that run lengthways along the nave. But I think the span is too large and the continuity of the roof void impeded. Who knows? It would be wonderful to venture up into that space.

So I have reverted to a trusses above "shell vaults" interpretation. We did see lots of examples of ceiling vaults built with the shallow flat bricks that predominate locally. Again, I would love to see Tuscan tradesmen constructing these vaults. One of the advantages of building a model from scratch with software like Revit is that you can create it "as it used to be". Whereas a point cloud just captures a moment in time with whatever alterations and clutter have accumulated over time. So I restored the high level windows along the aisle, on the assumption that they used to exist. Another open question, and there are many more to be asked.

So that is my version of San Giusto, Volterra as it stands today. I would love to explore some deeper questions. I haven't mentioned the question of the bell tower which seems to rest partly on the edge of a vault, nor the fact that I have omitted the lean-to structures either side of the "east end". These look to be later additions, but they could be altered versions of rooms that were there originally. The church was designed in 1628 though for some reason not consecrated until 1775. The style puzzles me a little. It is often described as Neoclassical or Renaissance, which I take to be generic terms. The date would put it in the Baroque period and it does strike me as a kind of very simple, "rustic" version of Baroque. But those are discussions for another day. Much to be done.