Take the ruthless purism of a Greek temple and dial it back a notch. Now you have the pragmatism of the Romans: a balance between formal beauty and practical convenience.

The Greek temple form, with a porch on all four sides is rare in the modern era. There are examples, but not so many.

The Roman type, with a porch at the front and shallow pilasters to maintain the rhythm on the other three sides is much more common. It works for banks, and for government buildings like the Virginia State Capitol. You can argue functional efficiency while maintaining simplicity, unity of form and truth to historic precedent.

I haven’t attempted to maintain a single family that morphs into multiple buildings just by typing in parameters. Perhaps I will walk back in that direction a little once I have a a dozen or so examples from which to generalise. For now, Roman pragmatism has jumped the blood brain barrier and infected my Revit strategy. The Virginia State Capitol, but Thomas Jefferson with Charles-Louis Clerisseau (who seems to have been a kind of “gun for hire”: architect, draughtsman, antiquary and painter of picturesque ruins)

So we are ‘saving as’ and adapting each family in an ad-hoc way. It’s an interesting journey. See how we have sidestepped the religious origins of the Roman Temple archetype. As we move into the industrial age, secular institutions begin to usurp the role of the church. Boundaries blur. The religious impulse finds other ways to express itself.

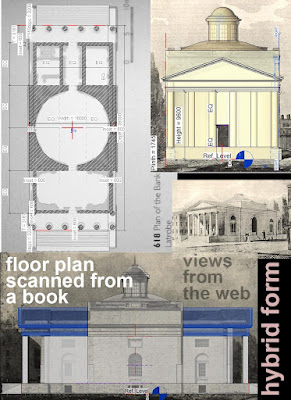

The Bank of Pennsylvania is dialed back yet another notch from purity of form. In a way it is more symmetrical, with porches at both ends, but not really. At the sides continuity breaks down. Arches suddenly make an appearance. (not yet modeled) No Greek precedent for that. Latrobe was English but of French Huguenot descent. He grew up in Yorkshire (like me) and was apprenticed to John Smeaton of Lighthouse fame.

For the bank he nested a mini-Pantheon inside his Roman temple, expressed externally as I a cube with a shallow dome and lantern pushing through in search of light.

I started with a rational solution to a parametric pediment, extended this into a Roman Temple and varied that theme to become Jefferson’s reworking of the temple form as a house for the abstract gods of democracy.

Latrobe pushed contingency much further in his “house of mammon”, hinting at a hybrid form. Am I engaged in a comparable dance of improvisation?

Mix and match stands in contrast to purism. Picturesque displaces the tyranny of Reason. Romanticism contends with Rationalism.

Faith v Works. Reason v Emotion. Art v Science. How do we integrate these dichotomies? Inevitably the way we build reflects these struggles within society. Architecture becomes a mirror for the human soul.