Probably my number one musical hero,

John Lee Hooker. I discovered him in my first year at university and was simply

blown away. These are scans of second hand LPs I bought back then and were

sitting in my house in Zimbabwe for the past 20 years. After some agonising I

decided against trying to ship them. I have mp3s and you can stream them if you

want. For the most part, as I get older, I prefer the versions that play in my

head. Bottled music, like bottled fruit, loses a lot in translation. So I just have

images, complete with my signature on the back. Partly a product of living in

communal houses.

His technique was deceptively simple and quite often he

would play through a whole song in one chord. This confused backing musicians

at times, who would try to go through the twelve bar changes based on his

vocals. The result can be quirky, but sets up a tension that is much more

effective than everyone just following a script.

He could make a single note shake you to your core, and

the tone of his voice... To die for. I always felt slightly embarrassed singing

his songs, but I had to try.

It's all about tone, both guitar and voice (not to

mention foot tapping) He could unleash a flurry of notes at speed, syncopate

the rhythm, lots of little tricks. But in the end it was tone. Raw emotion. We

all fall for virtuosity at times, especially when we're young, but ultimately

music was born out of deep emotional bonding, around a camp fire, somewhere in

Africa tens of thousands of years ago.

He could harness that power. In spades.

In 1983 I was 32 years old and I had

been in Zimbabwe for a year and a half, teaching building at Rusununguko

Secondary School. The long holidays were coming up and I had this idea to write

a little building workbook to express my ideas about injecting a bit more

creativity into the subject.

It had been conceived before independence as an option

for the less intelligent black students, preparing them for the idea of working

in the construction industry, or at least acquiring some skills that they could

use in the rural areas.

I don't want to be too hard on this. Given the

realities of the time it was an attempt by educators to offer something useful

to teenagers who had little chance of getting a desk job or going to

university. But the mood after independence was a bit different.

Certainly in my mind I wanted Building to be a viable

subject choice for students of all ability levels. That's who I had in my

classes and I taught that there are many different options within the building

sector to suit your abilities and interests. Also, whatever the future held for

you, a building course was a great way to learn to apply book learning to

practical situations. It could be Maths and Science, English, problem solving,

group collaboration. I thought it was a great integrative subject, and of

course I loved building.

Rusununguko was a Zimfep school. In theory at least

they aimed to give a balanced education with a mix of academic and practical

work. I took my draft booklet to the Zimfep head office in Harare and they

decided to run off a number of copies to distribute to schools.

I don't think they saw much use in the classroom, but

the idea was to stimulate thought and discussion among teachers at these

schools.

More pages from the building

workbook I wrote in 1983 after 18 months of hands-on teaching at an

experimental school on a farm in Zimbabwe. I was the only white face in that

community which inevitably gave me time to think about how I could weld

together my drawing skills, my time in UK laying bricks, and the teaching

experience.

There was no such thing as YouTube of course, nowhere

to go to see a visualisation of trowel skills for example. So I thought I was

doing something quite ground-breaking.

When I was doing my crash course in bricklaying in

Sheffield with Mr Cox he would give us little dry bonding problems out on the

practice ground. I just used to love this. Have you grasped the basic

principles well enough to figure out how to handle a new and unexpected

situation?

In Zimbabwe 7 or 8 years later, involved in an educational experiment and totally immersed in a new and challenging experience, I wanted to share the excitement of this hands-on problem solving with eager young African teenagers with a real hunger to learn.

It's so interesting to read something I wrote half a lifetime ago, paired with a cheeky little illustration to convey the ideal of Education With Production. Also the cover of a book I was using in my attempts to learn Shona. Comrade Andrew is the name I was known by at Rusununguko during my first two years in Zimbabwe.

Photographs from 1982 when we were

still trying to maintain the illusion that the students could build their own

school. I was a volunteer building teacher at Rusununguko, struggling with

class sizes of 80 at times.

Twenty minutes walking down to the "new

site." A mad scramble to grab the few tools available. 40 minutes of

chaotic work. Wash the tools. Walk back to the "old site" Zero chance

to develop skills in a systematic way.

After one term like this I fought hard to bring class

sizes down and involve the whole class in a learning experience. Adult teams

were brought in to build most of the buildings and some kind of sanity was

restored.

Having said all that, it was an amazing experience for

me to be immersed in a community of returned refugees, to be stretched to the

limits of my own abilities and to figure out how to ride the daily

roller-coaster.

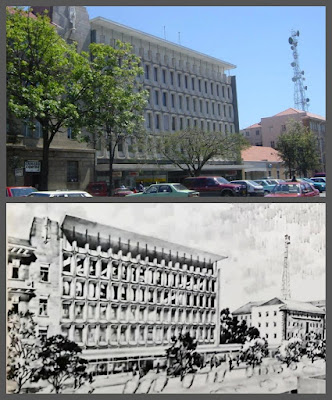

Natural beauty of sunsets with the radio mast on a

distant ridge. Babysitting while working on a classroom block. My trademark

white boiler suit and the mattress on the floor which was my sleeping space for

the first year. Telltale overage students given a chance to complete secondary

school on retuning so Zimbabwe from camps in Mozambique.