Early 2013 and I was building up towards an

epic trip to attend conferences in London and New Zealand, visiting friends and

family along the way.

For the “BIM Show Live” event in London, I

wanted to depict BIM as a continuation of the grand tradition of DRAWING, aka

“visual thinking”. Matisse cut up pieces

of coloured paper with scissors to create 2d images. Reitveld cut up pieces of cardboard to design

3d furtniture. There is an incredibly

rich vein running through our history, stretching back at least 30 thousand

years. We create “models”,

representations of reality, diagrams, solidified thoughts.

So here is a post that lays out that idea:

first of all some historical musings, then some of my attempts to do “BIM

pencil stuff” aka thinking aloud with Revit.

https://grevity.blogspot.com/2013/02/what-do-you-mean-just-drawing.html

For New Zealand, (which was to be my first

Revit Technology Conference as a Speaker) I had set myself ridiculously

ambitious goals. There were at least 4

separate 2 hour sessions condensed into one 75 minute PowerPoint. I see conferences as opportunities to

motivate myself, chances to tackle something challenging and see it through to

a conclusion.

I chose three office buildings from the

history of architecture, set out to model them in Revit, and then to tell a

fascinating, interwoven story … ranging from design analysis, via structural

form and environmental performance, to social and political significance.

Casa del Fascio is a famous work of Italian

Rationalism from the 1930s. Every now

and then I return to this model and take it a little further. Always something new to discover.

https://grevity.blogspot.com/2013/03/i-spent-weekend-preparing-for-rtc.html

I had bought a Microsoft Surface … the very

first model. I wanted to integrate hand

drawing into my digital world, so I was playing around with the touch screen,

with OCR, with cloud syncronisation between devices. It has taken a few years for this to become

an everyday reality. Partly because the

technology needed to get better, partly because you need to act it out in

physical reality, to adapt your hands, eyes & brain to new possibilities.

Learning takes time. Thinking is an

embodied process.

I was about the role of suppliers and

contractors in BIM processes. 7 years ago most people thought Revit was a

clever software tool for architects. Builders, Suppliers & Sub-contractors

didn’t see why it would impact the way that they worked. I sketched a diagram with irreverent acronyms

to explore the idea of digital collaboration across the whole industry.

This is starting to happen. But in my view we still have a long way to

go.

https://grevity.blogspot.com/2013/03/surface-effects.html

My day job involved trying to bring our

Schools Team into the world of BIM. During

that work I applied my experience with adaptive components to modelling a

parametric slatted screen. It was fun,

but my cleverness got the better of me.

There was a far simpler solution using the Curtain Wall tool.

It’s easy to get the idea that you should

do everything “the clever way,” Not

really. Keep it simple. Only bring the heavy guns out when you really

need them.

https://grevity.blogspot.com/2013/03/primal-screen.html

In the next post I seek to justify my

“cleverness” by imagining a situation where the complexity of my solution would

really be needed. This was a fun

exploration, but not very convincing as a “real-life” example. I tried to gloss over this be showing an

image of C.F.A. Voysey’s deceptively simple stair screen. But in the end that just proves the value of

a simple solution.

The Orchard, Chorleywood. Difficult to

explain why this is such an impressive design.

Definitely something that should be explored with the BIM pencil.

https://grevity.blogspot.com/2013/03/curve-that-screen.html

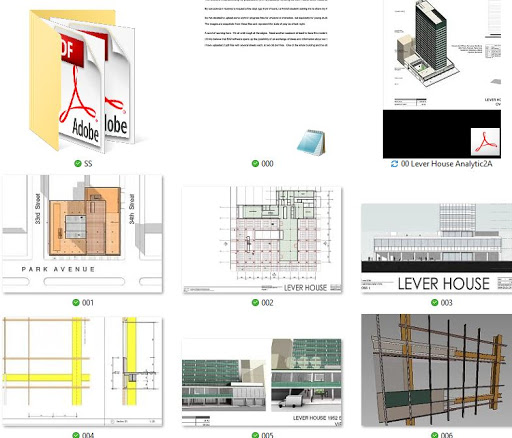

The second office building that I chose for

my RTC NZ presentation was Lever House, the original “glass box” office tower

from 1950s New York. Here’s a sentence

that I wrote.

“I firmly

believe that BIM software opens up the possibility of an exchange of ideas and

information about our built past. far beyond anything currently available.”

Still

working on that 😊

https://grevity.blogspot.com/2013/03/pull-that-lever.html

From time to time I share some images from

work that we are doing at GAJ. There are

confidentiality issues to skirt around of course, but sometimes I feel that we

have produced something that could inspire others to push the boundaries of BIM

a little further.

I stopped using Sketchup 15 years ago. Sadly many young architects think that BIM

authoring tools lack the fluidity to express design ideas, especially in the

early stages of a project. My day-job

role is mostly focused on the production stage, but every now and then I get a

chance to show that Revit may not be so clunky after all.

Fluency is a state of mind and it is

acquired by putting in the time to learn your trade. I’m not dissing Sketchup. I used it in the early days, before Google

bought it out. But once I got my hands

on Revit there didn’t seem to be any point in starting a project off with one

tool only to begin again from scratch a few weeks later.

https://grevity.blogspot.com/2013/04/i-just-want-to-share-some-of-revit.html

Of course one reason that Sketchup gets

used so much is the available library of “assets” Easy to find furniture, household items,

trees etc. Also lots of stylised people

doing all the different things you might want the inhabitants of your

perspectives to be doing. RPC people are

great, but you only get so many, (out of the box) and they don’t look all that

brilliant in shaded views.

I set about creating some Sketchup-style

people for Revit and shared them. I

invited my audience to join in the fun and we did make some progress. Arguable, Enscape assets have made this work

somewhat redundant, but maybe there is still a place for flat people. Everyone loves the clarity of a simple line

drawing, don’t they?

https://grevity.blogspot.com/2013/04/flat-people.html

I still love Darwin’s “Simple line drawing”

with the caption “I think.” It’s crude

and clumsy by artistic standards, but it captures the essence of thinking

diagrammatically on a sheet of paper.

“Tomorrow

morning, I get on a plane to London.”

That was an epic journey. Seems

so long ago. I met so many interesting

people along the way, still remember Alfredo introducing himself in Auckland

and it was great to stay with my sister there, finally.

https://grevity.blogspot.com/2013/04/grevity-world-tour.html

From my BIM Show Live session …

Life is a journey. Mine

has taken me to all kinds of interesting places: geographically, socially,

intellectually. Visual thinking has played a central role in my life and the

ancient tradition of drawing has been a constant source of inspiration. I

like to draw ... and in recent years BIM has become my favourite

"pencil."

BIM is

not a radical break with the past. It’s an amazing tool, but no more radical

than perspective or orthographic projection were in their day. When we read

Shakespeare we don’t think, “if only he had a word processor, he could have

done so much more”. It’s not what you’ve got, it’s the way that you use it.

https://grevity.blogspot.com/2013/05/bsl2013.html

https://grevity.blogspot.com/2013/05/bsl-download.html