I've called Project Soane, a detective story and a jigsaw puzzle before, but perhaps it is better described as a Treasure Hunt: hidden clues, buried gold, one legged parrots ? Seriously though, up to a couple of weeks ago I assumed that three out of four elevations inside the Bullion Yard were down to Sampson and Taylor, but as I looked more carefully at the vast hoard of reference material we have collected into a Box account (our treasure chest) … I began to realise just how much effort Soane put into remodeling the entire space.

This drawing of the West Side shows Sampson's fenestration in yellow on top of Soane's. Basically there are 4 bays superimposed on three. So it wasn't just a case of demolishing the back wall and rebuilding it as a shallow curve. He must have taken them all down, probably one at a time, and rebuilt them with a different bay spacing. But it doesn’t end there. I finally convinced myself that he dropped the level of this courtyard down one floor to basement level.

Let's start with the curved wall. In Sampson's successful competition design, the bullion passage comes in from the side to enter through the most northerly arch in the East façade. Now the site slopes from front to back, so the lane coming up from Bartholomew Way would have to ramp up a couple of feet, but that's a fairly gentle slope, and all the better to carry the rain away methinks.

However, when Soane bought out all the remaining properties in that city block, acting as agent for the Bank, he was able to relocate the Bullion passage. His scheme for a North East extension was ingenious, but required lengthy negotiations with the Building Committee to persuade them to spend rather more money than they originally anticipated. In order to open up the middle of the site, and make space for a rational planning scheme, he had to demolish Taylor's file storage building (Consols Library) and rebuild it in the top corner of the site. This allowed just enough space for a large Transfer Office between the library and the Bank Stock Office, but only by blocking off the side lane.

Now he was free to create a much grander bullion route, a truly symbolic statement for this activity that lay at the heart of the Bank's foundation: bringing in gold to finance the government's war debts, in exchange for pieces of paper (stocks and bonds) Lothbury heads North West at an awkward angle, but luckily a perpendicular line from the centre of the Lothbury façade hits the centre of the Bullion Yard quite nicely.

There is a rather messy sketch showing what happens if you leave the North Façade of the yard as a straight line. The cranked end solution is really horrible and I wonder if Soane produced this drawing just to prove to the Directors that they had to rebuild that façade to a shallow curve. But Lothbury is also some six feet below Threadneedle Street. For Soane this was another welcome opportunity. He could ramp down gently a couple of feet and excavate the entire bullion yard down to cellar level. Now you could unload bullion and feed it directly into the vaults below.

I have been puzzled for a long time by Sampson's section, which doesn't show anything below ground level. And yet his plan clearly indicates the light well in the Entrance Court that is still there in photographs taken almost 200 years later. I think there must have been an undercroft under the whole building. That was a standard approach to foundations in those days. Survey drawings of the cellars produced much later by Soane suggest that for the most part his work and Sampson's were built over brick vaulted cellars, but that Taylor's transfer halls were constructed with cheaper and shallower foundations.

Sampson's rear courtyard had open arcades along two sides. They are primary means of circulation. The one on the west side leads through to a triangular yard at the back where the privies were located. But there are no arcades along the other two sides. To cross from east to west you would have to use the yard. So the yard must have been at ground floor level, gave or take. I don't remember seeing any mention of the fact that Soane excavated this yard in the accounts that I have read. Maybe I should go through them again carefully. But maybe it's something you don't realise until you have spent a couple of years using the BIM pencil to search for hidden treasure.

So let's get to the bay sizes. Soane has a wider passage. I'm guessing that the constriction of Sampson's arch at the point of entry had been a sore point for some years. In any case, a double storey archway such as Soane now had would have looked ridiculous with the same width as Sampson's arcade. So his curved wall had two broad, arched windows balancing out the archway. It's not completely symmetrical, but it's regular enough.

From here you just have to persuade the committee that the other three facades are going to look out of place. Perhaps they are going to be unstable anyway when you commence excavation. Whatever reasoning Soane used (and unfortunately the records of meetings for many of Soane's years are missing) he succeeded in his plan to unify the treatment. Or did he? Suddenly I remembered something that I noticed long ago but couldn't understand. It's a photo looking down the tunnel, showing misalignment between ground and upper floors. Were the side elevations also misaligned? Difficult to say. For the moment I'm going to leave the model fully lined up, on the assumption that this was what Soane "really intended".

The windows echo Sampson and Taylor's Palladian efforts around the garden court, but in a much simplified manner. It’s all handled in the timber of frame, just a subtle thickening to allow for the boxes that carry the counterweights for the sliding sashes. But you still have the effect of a glass arch spanning between the two sidelights. I said before that this glazing was probably Taylor's contribution, & here is my evidence. Sampson's pencil drawings show a conventional Palladian window with no glazing over the arch.

There are variations on Soane's design scattered around his later work: (Lothbury Court, the Accountants Office) but he also glazed large arched windows more simply at times, with a rectangular grid. Basically it comes down to whether there are opening lights or not. A large fixed window can be glazed with a simple grid of metal glazing bars.

Taylor's West Wing, blocks off one corner of the Pay Hall. The glazing over the arch is perhaps a compensation for this, but it's also an attempt to match his treatment of the new Court Room windows. It looks like he also added an upper window on the side that isn't blocked.

I accidentally created this ghostly cross section that blurs across the period of these 3 architects. It was just a working image to help me scale the model of Sampson's bank that I knocked up quickly over the past week. But then I realised that it conveys quite a lot.

I also decided to add the images of windows that I snapped in St Louis. On the left you have a version of the approach that Sampson & Taylor followed: masonry arches and columns to create a rhythmic group of openings that can be separately glazed. On the right is Soane's method, setting up his rhythms in a more subtle way with variations in the framing.

So here are the basic relationships between the areas I have been working on for the past few weeks. You can see that the New Court Room is on axis with the old one, projected out to the West, dropped down to the ground and substantially enlarged.

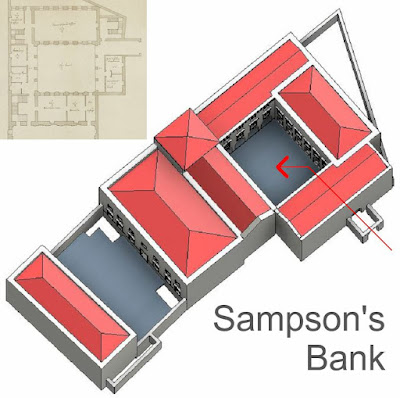

This is model of Sampson's Bank as it stands. Probably I will leave it now and come back later. It's served the current purpose of understanding how Bullion Court was modified by Soane.

I quite like the way the city block is represented as bare earth. The warren of alleys and narrow courts, with its workshops, inns, houses, workshops, stables and church are probably best left to the imagination.

And so the treasure hunt continues. Who knows what awaits next week? Surely there can't be many more surprises like the discovery that Soane excavated the Bullion Court a full storey. But you never know.

Here is an odd image to finish with. It's an old version of the Bank Model linked in to my new model of Sampson's original structure. Most of the links are missing (screen walls, consols transfer office) and I've given it a bit of transparency. There are areas of flat roof where I hadn't yet worked out what was going on. So there's a sense of evolution here on two levels: the growth of the bank itself, and the traces of my own fumblings to dig up that history.

This drawing of the West Side shows Sampson's fenestration in yellow on top of Soane's. Basically there are 4 bays superimposed on three. So it wasn't just a case of demolishing the back wall and rebuilding it as a shallow curve. He must have taken them all down, probably one at a time, and rebuilt them with a different bay spacing. But it doesn’t end there. I finally convinced myself that he dropped the level of this courtyard down one floor to basement level.

Let's start with the curved wall. In Sampson's successful competition design, the bullion passage comes in from the side to enter through the most northerly arch in the East façade. Now the site slopes from front to back, so the lane coming up from Bartholomew Way would have to ramp up a couple of feet, but that's a fairly gentle slope, and all the better to carry the rain away methinks.

However, when Soane bought out all the remaining properties in that city block, acting as agent for the Bank, he was able to relocate the Bullion passage. His scheme for a North East extension was ingenious, but required lengthy negotiations with the Building Committee to persuade them to spend rather more money than they originally anticipated. In order to open up the middle of the site, and make space for a rational planning scheme, he had to demolish Taylor's file storage building (Consols Library) and rebuild it in the top corner of the site. This allowed just enough space for a large Transfer Office between the library and the Bank Stock Office, but only by blocking off the side lane.

Now he was free to create a much grander bullion route, a truly symbolic statement for this activity that lay at the heart of the Bank's foundation: bringing in gold to finance the government's war debts, in exchange for pieces of paper (stocks and bonds) Lothbury heads North West at an awkward angle, but luckily a perpendicular line from the centre of the Lothbury façade hits the centre of the Bullion Yard quite nicely.

There is a rather messy sketch showing what happens if you leave the North Façade of the yard as a straight line. The cranked end solution is really horrible and I wonder if Soane produced this drawing just to prove to the Directors that they had to rebuild that façade to a shallow curve. But Lothbury is also some six feet below Threadneedle Street. For Soane this was another welcome opportunity. He could ramp down gently a couple of feet and excavate the entire bullion yard down to cellar level. Now you could unload bullion and feed it directly into the vaults below.

I have been puzzled for a long time by Sampson's section, which doesn't show anything below ground level. And yet his plan clearly indicates the light well in the Entrance Court that is still there in photographs taken almost 200 years later. I think there must have been an undercroft under the whole building. That was a standard approach to foundations in those days. Survey drawings of the cellars produced much later by Soane suggest that for the most part his work and Sampson's were built over brick vaulted cellars, but that Taylor's transfer halls were constructed with cheaper and shallower foundations.

Sampson's rear courtyard had open arcades along two sides. They are primary means of circulation. The one on the west side leads through to a triangular yard at the back where the privies were located. But there are no arcades along the other two sides. To cross from east to west you would have to use the yard. So the yard must have been at ground floor level, gave or take. I don't remember seeing any mention of the fact that Soane excavated this yard in the accounts that I have read. Maybe I should go through them again carefully. But maybe it's something you don't realise until you have spent a couple of years using the BIM pencil to search for hidden treasure.

So let's get to the bay sizes. Soane has a wider passage. I'm guessing that the constriction of Sampson's arch at the point of entry had been a sore point for some years. In any case, a double storey archway such as Soane now had would have looked ridiculous with the same width as Sampson's arcade. So his curved wall had two broad, arched windows balancing out the archway. It's not completely symmetrical, but it's regular enough.

From here you just have to persuade the committee that the other three facades are going to look out of place. Perhaps they are going to be unstable anyway when you commence excavation. Whatever reasoning Soane used (and unfortunately the records of meetings for many of Soane's years are missing) he succeeded in his plan to unify the treatment. Or did he? Suddenly I remembered something that I noticed long ago but couldn't understand. It's a photo looking down the tunnel, showing misalignment between ground and upper floors. Were the side elevations also misaligned? Difficult to say. For the moment I'm going to leave the model fully lined up, on the assumption that this was what Soane "really intended".

The windows echo Sampson and Taylor's Palladian efforts around the garden court, but in a much simplified manner. It’s all handled in the timber of frame, just a subtle thickening to allow for the boxes that carry the counterweights for the sliding sashes. But you still have the effect of a glass arch spanning between the two sidelights. I said before that this glazing was probably Taylor's contribution, & here is my evidence. Sampson's pencil drawings show a conventional Palladian window with no glazing over the arch.

There are variations on Soane's design scattered around his later work: (Lothbury Court, the Accountants Office) but he also glazed large arched windows more simply at times, with a rectangular grid. Basically it comes down to whether there are opening lights or not. A large fixed window can be glazed with a simple grid of metal glazing bars.

Taylor's West Wing, blocks off one corner of the Pay Hall. The glazing over the arch is perhaps a compensation for this, but it's also an attempt to match his treatment of the new Court Room windows. It looks like he also added an upper window on the side that isn't blocked.

I accidentally created this ghostly cross section that blurs across the period of these 3 architects. It was just a working image to help me scale the model of Sampson's bank that I knocked up quickly over the past week. But then I realised that it conveys quite a lot.

I also decided to add the images of windows that I snapped in St Louis. On the left you have a version of the approach that Sampson & Taylor followed: masonry arches and columns to create a rhythmic group of openings that can be separately glazed. On the right is Soane's method, setting up his rhythms in a more subtle way with variations in the framing.

So here are the basic relationships between the areas I have been working on for the past few weeks. You can see that the New Court Room is on axis with the old one, projected out to the West, dropped down to the ground and substantially enlarged.

This is model of Sampson's Bank as it stands. Probably I will leave it now and come back later. It's served the current purpose of understanding how Bullion Court was modified by Soane.

I quite like the way the city block is represented as bare earth. The warren of alleys and narrow courts, with its workshops, inns, houses, workshops, stables and church are probably best left to the imagination.

And so the treasure hunt continues. Who knows what awaits next week? Surely there can't be many more surprises like the discovery that Soane excavated the Bullion Court a full storey. But you never know.

Here is an odd image to finish with. It's an old version of the Bank Model linked in to my new model of Sampson's original structure. Most of the links are missing (screen walls, consols transfer office) and I've given it a bit of transparency. There are areas of flat roof where I hadn't yet worked out what was going on. So there's a sense of evolution here on two levels: the growth of the bank itself, and the traces of my own fumblings to dig up that history.