This is part 2 of a BIM Breakfast talk given on 24th November in Dubai.

You don't have to be a gifted artist to gain benefits from visual thinking. This example is from Newton's scientific notes. Even with his relatively crude drawing technique the idea of light being split into a spectrum of colours as it passes through a prism is conveyed much more vividly than would be possible with a purely verbal description.

You don't have to be a super-geek to do great things with BIM. It's the thought that counts. Newton used drawing to clarify his understanding of optics, the relationship between white light and the rainbow colours of the spectrum. Clumsy technique but ground breaking ideas.

More examples from non artists. Now we are entering the age of the industrial revolution, an explosion of software and hardware that ultimately led to today's digital world.

Stephenson's rocket converted fossil fuel into forward motion and enabled the first railway line that carried cotton cloth from Manchester Mills to the port of Liverpool. Darwin was also interested in fossils, but for different reasons. Notice the phrase "I think" at the top right. Here he is thinking aloud by means of a diagram. Once again, the technique is crude, but the power of visual thought is crystal clear.

Looking back for a moment to Durer and a pencil drawing of the great Humanist thinker Erasmus. The technology he is using to capture his thoughts before they slip from memory dates back to ancient Egypt: a reed cut by a knife and split at it's end to allow the ink to flow. Notice how he holds the ink pot in one hand to allow regular dipping of the pen.

Here is a piece of hardware that lasted 3000 years, from ancient egyptian times to the beginning of the 19th century. Then we started to burn fossil fuels, using up capital that had sat in the ground for 200 million years in the space of 200. Eating up a million years every 12 months. Certainly we are the cleverest animals that ever lived.

The industrial revolution swept swept ancient traditions away overnight. Mass produced steel nibs poured out of Birmingham in their thousands. No more reeds or goose feathers.

And here it is, now a museum piece. It's just a reed pen made of thin steel sheet, but you can make them by the thousand and ship them out in small boxes. They last longer, create thinner and more consistent lines.

All this was made possible by digging up coal. Fossil fuels that had taken hundreds of millions of years to form, burned away in a few decades. Only recently have we started to understand how rapidly we are consuming our natural capital. And yet we continue to behave as if continuous growth and innovation was the answer to all our dreams.

Bigger, better, faster has become an end in itself. We all know that it is not sustainable, but we continue to put on our business blinkers and gallop off into the future.

And so to the twentieth century and technology has mushroomed. Human population has exploded and we now dominate the earth like no species has ever done before. The most successful species the world has ever seen. But for how long? We all know that it can't last for ever? We have become addicted to growth and change. Bigger, better, faster. It's like a drug. We don't know how to stop.

Don't get me wrong, I love computers. I can't wait for the latest version of Revit to come out each year. And I enjoy using BIM to deliver projects for GAJ. But at the back of my mind I know there's an elephant in the room. And in my spare time, I try to use BIM in unusual ways, to connect back to the ancient tradition of visual thinking and artistic expression.

So here are some of my attempts to use BIM as a pencil.

I don't have an answer to all our problems, but I do have a suggestion. Take off the business blinkers, stand back and take a broader view. Take a cue from great artists of the past. Use BIM like a pencil. Don't limit it's use to the narrow confines of business contracts. Treat it as a medium that can range across the whole gamut of human thought, from art to science to education, from historical research to idle doodling and optical illusions.

Let me give some examples from my own work.

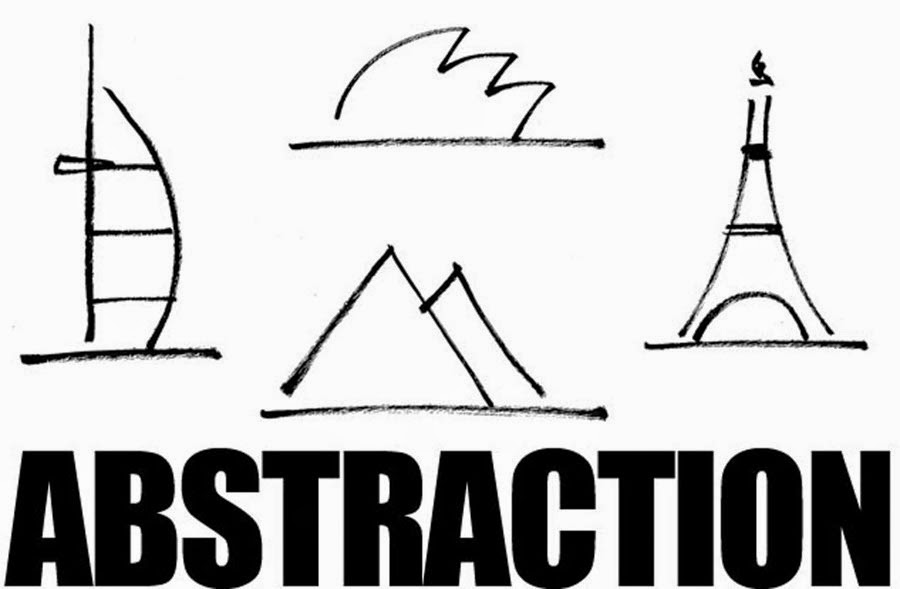

Lever House is a modern movement classic, built when I was a toddler. Abstraction & simplification. How far can you boil down the idea behind a design concept without losing its essence ? How would you tackle this challenge in a BIM way ?

Drawing/modelling to understand how a building works. Asking questions, probing the finer details. Understanding the kit of parts, sequence of trades. What can a sixty year old building teach us ? BIM is a terrific way to find out.

Casa del Fascio, a controversial tour de force by a young Italian idealist, carried away by nationalist rhetoric. I used a Chess board analogy to illustrate the sequence of moves by which a regular grid becomes inflected to create a more complex functional arrangement of spaces. Note the interplay of structural frame and infill panels, transforming a box into a sculptural form that changes as you walk around it. One of the few 1930s buildings that looks as if it could have been designed yesterday.

I have been developing this one as an exercise for students of architecture who wish to aqcuire some software skills at the same time as investigating the subtleties of this deceptively simple office building with its triangular voids that spiral around the outside connecting office floors together and allowing light and air to penetrate and circulate.

Instead of teaching students about BIM, perhaps we would be better encouraging students to use BIM as a thinking tool via self-directed research and exploration.

Baroque architecture is known for its complex geometries. In this study I used the parametric modelling capabilities of the software to investigate the underlying relationships, searching for an appropriate level of simplification. I believe that hands-on exercises like this, where students use BIM tools to explore architecture of the past would have much more value than a series of lectures about "the role of BIM in the modern construction industry".

This is a place that I visited in the late 1970s and it was a fascinating experience to recreate it as a digital model. I discovered regularities in the setting out of the seats that had never been clear to me until I undertook this exercise, using BIM like a pencil to take me on a voyage of discovery.

I seriously need to start my weekend, and there's another BIM breakfast coming up that I have to prepare for, so I'll break it off there and finish this rambling rose off next week. I'm hoping some of this strikes a chord with somebody out there.

You don't have to be a gifted artist to gain benefits from visual thinking. This example is from Newton's scientific notes. Even with his relatively crude drawing technique the idea of light being split into a spectrum of colours as it passes through a prism is conveyed much more vividly than would be possible with a purely verbal description.

You don't have to be a super-geek to do great things with BIM. It's the thought that counts. Newton used drawing to clarify his understanding of optics, the relationship between white light and the rainbow colours of the spectrum. Clumsy technique but ground breaking ideas.

More examples from non artists. Now we are entering the age of the industrial revolution, an explosion of software and hardware that ultimately led to today's digital world.

Stephenson's rocket converted fossil fuel into forward motion and enabled the first railway line that carried cotton cloth from Manchester Mills to the port of Liverpool. Darwin was also interested in fossils, but for different reasons. Notice the phrase "I think" at the top right. Here he is thinking aloud by means of a diagram. Once again, the technique is crude, but the power of visual thought is crystal clear.

Looking back for a moment to Durer and a pencil drawing of the great Humanist thinker Erasmus. The technology he is using to capture his thoughts before they slip from memory dates back to ancient Egypt: a reed cut by a knife and split at it's end to allow the ink to flow. Notice how he holds the ink pot in one hand to allow regular dipping of the pen.

Here is a piece of hardware that lasted 3000 years, from ancient egyptian times to the beginning of the 19th century. Then we started to burn fossil fuels, using up capital that had sat in the ground for 200 million years in the space of 200. Eating up a million years every 12 months. Certainly we are the cleverest animals that ever lived.

The industrial revolution swept swept ancient traditions away overnight. Mass produced steel nibs poured out of Birmingham in their thousands. No more reeds or goose feathers.

And here it is, now a museum piece. It's just a reed pen made of thin steel sheet, but you can make them by the thousand and ship them out in small boxes. They last longer, create thinner and more consistent lines.

All this was made possible by digging up coal. Fossil fuels that had taken hundreds of millions of years to form, burned away in a few decades. Only recently have we started to understand how rapidly we are consuming our natural capital. And yet we continue to behave as if continuous growth and innovation was the answer to all our dreams.

Bigger, better, faster has become an end in itself. We all know that it is not sustainable, but we continue to put on our business blinkers and gallop off into the future.

Don't get me wrong, I love computers. I can't wait for the latest version of Revit to come out each year. And I enjoy using BIM to deliver projects for GAJ. But at the back of my mind I know there's an elephant in the room. And in my spare time, I try to use BIM in unusual ways, to connect back to the ancient tradition of visual thinking and artistic expression.

So here are some of my attempts to use BIM as a pencil.

I don't have an answer to all our problems, but I do have a suggestion. Take off the business blinkers, stand back and take a broader view. Take a cue from great artists of the past. Use BIM like a pencil. Don't limit it's use to the narrow confines of business contracts. Treat it as a medium that can range across the whole gamut of human thought, from art to science to education, from historical research to idle doodling and optical illusions.

Let me give some examples from my own work.

Lever House is a modern movement classic, built when I was a toddler. Abstraction & simplification. How far can you boil down the idea behind a design concept without losing its essence ? How would you tackle this challenge in a BIM way ?

Drawing/modelling to understand how a building works. Asking questions, probing the finer details. Understanding the kit of parts, sequence of trades. What can a sixty year old building teach us ? BIM is a terrific way to find out.

Casa del Fascio, a controversial tour de force by a young Italian idealist, carried away by nationalist rhetoric. I used a Chess board analogy to illustrate the sequence of moves by which a regular grid becomes inflected to create a more complex functional arrangement of spaces. Note the interplay of structural frame and infill panels, transforming a box into a sculptural form that changes as you walk around it. One of the few 1930s buildings that looks as if it could have been designed yesterday.

I have been developing this one as an exercise for students of architecture who wish to aqcuire some software skills at the same time as investigating the subtleties of this deceptively simple office building with its triangular voids that spiral around the outside connecting office floors together and allowing light and air to penetrate and circulate.

Instead of teaching students about BIM, perhaps we would be better encouraging students to use BIM as a thinking tool via self-directed research and exploration.

Baroque architecture is known for its complex geometries. In this study I used the parametric modelling capabilities of the software to investigate the underlying relationships, searching for an appropriate level of simplification. I believe that hands-on exercises like this, where students use BIM tools to explore architecture of the past would have much more value than a series of lectures about "the role of BIM in the modern construction industry".

This is a place that I visited in the late 1970s and it was a fascinating experience to recreate it as a digital model. I discovered regularities in the setting out of the seats that had never been clear to me until I undertook this exercise, using BIM like a pencil to take me on a voyage of discovery.

I seriously need to start my weekend, and there's another BIM breakfast coming up that I have to prepare for, so I'll break it off there and finish this rambling rose off next week. I'm hoping some of this strikes a chord with somebody out there.