VANILLA PROVE THYSELF

When Robie House was nearing completion, Frank Lloyd Wright had spent the best part of two decades building houses in and around Chicago. It stands like a ship in dry dock, poised above the street and was for Wright the ultimate expression of his vision of a new type of house, suited to the Prairie, with it's horizontal lines and overhanging roofs.

Having achieved his goal, Wright was ready to move on, abandon wife and family, take up with the wife of one of his clients and head for Europe (via Wisconsin). What else would you expect from a creative genius, driven by the desire to do things that "never happened before" ?

Although we are beginning to question this notion of the creative superhero it remains central to the world-view of industrial society. We idolise highly competitive, egotists like Wright, Steve Jobs, Ronaldo, Donald Trump. We love to believe that they have changed the world forever, invented new ways of being, expanded the art of the possible. But perhaps it is just a game, part of the never-ending spiral by which our consumer society fritters away the resource capital that our world has accumulated over hundreds of millions of years.

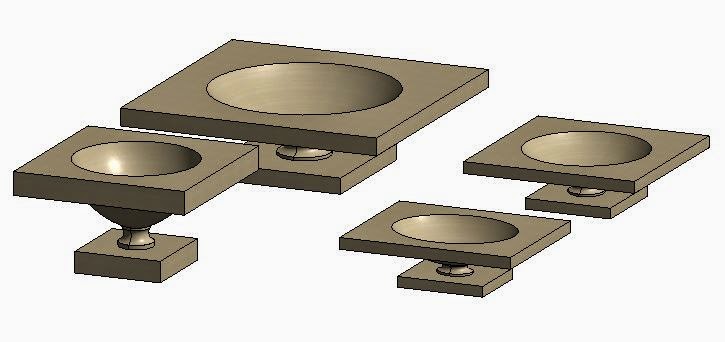

I am exploring two ways of making stuff: Vanilla & Point World. We have been using mass profiles hosted on a straight-line rig, to make a parametric planting bowl, specifically the one that Wright designed for Robie House. I want to go on and use this planter as a metaphor for Wright's creative process. He churned out houses by the dozen, endless variations on a theme. Most of them featured long low walls, spreading out like the roots of a tree, anchoring the house to it's site. And to accent these garden walls, two or three strategically placed planting urns.

And just like his houses, these planters re-invent themselves with each new commission. He couldn't stop fiddling, exploring new combinations of materials, structural gymnastics, different roof pitches. I never thought much about the planters until I visited some of his Prairie Houses, 2 or 3 weeks ago. Lately they have become something of a passion.

This one from the Heurtley House features a square base, then a cross, and finally a circular bowl. These are the three motifs in the logo he used during his Oak Park period.

My third Point-World planter is from his own house & studio. Built using a loan from Sullivan, this was his base right up to the Robie design: the family home he abandoned when he left Oak Park with Mamma Cheney. The planters are outside the entrance to the studio, itself an addition to the original house.

Louis Sullivan was his mentor and the source of some of his design ideas, particuarly the obsession with ornamental detail which can be a little embarassing to those who like to claim him as a modernist. But perhaps the more important skill he acquired from Sullivan was the ability to harness a team of draughtsman and drive them like a maniac towards his goals.

We idolise the creative artist, but in reality most of them ran studios. From Brunellischi to Gehry, the "great man" produces master-works from an assembly line, often using cheap semi-volunteer labour and almost always claiming the credit (and if you are Steve Jobs, the copyright) This is not to belittle the skill and vision of such men. The draughtsman is always free to set up on his own, perhaps by breaking his contract, as Wright did to Sullivan when he designed his "Bootleg Houses" less than a block from his own house, while serving out the 5 years exclusive service he had contracted in return for the building loan.

There are many more Wrightian planters. Please feel free to send me examples. Here are a few.

Winslow House was the first of the houses Wright designed after breaking with Sullivan. The house itself could almost have been by Sullivan, and the planter is conventionally classical. From here on the urns become more abstracted and geometric.

But what can Vanilla do ? (the challenge in my title) Can we achieve the same scalability using standard Family Editor geometry ? I chose the Nathan G Moore house.

The planter may date from the renovation that followed a fire more than 20 years after the original design. Difficult to be sure. The house itself is rather fussy and steep-pitched, not at all typical of his mature prairie style, whereas the planter is somewhat simpler.

Whereas Point World relies on the Normalised Curve Parameter (NCP) for much of its scalability, Vanilla prefers Reference Planes and equalisation constraints.

The formulae for isolating "Height" and "Slenderness" as the 2 primary user inputs are common to both methods however.

I didn't attempt a "Depth Factor" in Vanilla. Firstly I don't think it can be done. Secondly it's questionable how useful it is in this particular case. To be honest the oval/oblong versions of the planter look a little odd.

So what's the verdict? I enjoyed pitting the two worlds against each other on a similar task. I think the Point-World approach to scaling is more elegant, but Vanilla families are more servicable at present for use in real projects.

I had to cheat a little to get the various segments defining my vanilla revolve to snap to grid intersections. The NCP approach makes small adjustments much easier to achieve. Equalised dimensions are a little crude in comparison. I ought to mention that the Vanilla method makes use of the ability of splines to scale proportionately when their two ends are stretched apart.

All in all, I don't think there's a clear winner: just 2 different methods for making stuff that are worth practising and perfecting. Sometimes one will suit your needs better, sometimes the other. Point World can make shapes that are impossible with Vanilla. Point World only exsists (at present) in family templates that are not ideally suited to objects like planters, furniture, or plumbing fixtures.

So "viva la difference" and keep playing with both methods. Hope you found this useful. And if you are a Frank Lloyd Wright fan, please don't take offence. He was a lovable rogue, by all accounts and I prefer to love him "warts and all" rather than worship at the feet of my idol.

When Robie House was nearing completion, Frank Lloyd Wright had spent the best part of two decades building houses in and around Chicago. It stands like a ship in dry dock, poised above the street and was for Wright the ultimate expression of his vision of a new type of house, suited to the Prairie, with it's horizontal lines and overhanging roofs.

Having achieved his goal, Wright was ready to move on, abandon wife and family, take up with the wife of one of his clients and head for Europe (via Wisconsin). What else would you expect from a creative genius, driven by the desire to do things that "never happened before" ?

Although we are beginning to question this notion of the creative superhero it remains central to the world-view of industrial society. We idolise highly competitive, egotists like Wright, Steve Jobs, Ronaldo, Donald Trump. We love to believe that they have changed the world forever, invented new ways of being, expanded the art of the possible. But perhaps it is just a game, part of the never-ending spiral by which our consumer society fritters away the resource capital that our world has accumulated over hundreds of millions of years.

I am exploring two ways of making stuff: Vanilla & Point World. We have been using mass profiles hosted on a straight-line rig, to make a parametric planting bowl, specifically the one that Wright designed for Robie House. I want to go on and use this planter as a metaphor for Wright's creative process. He churned out houses by the dozen, endless variations on a theme. Most of them featured long low walls, spreading out like the roots of a tree, anchoring the house to it's site. And to accent these garden walls, two or three strategically placed planting urns.

And just like his houses, these planters re-invent themselves with each new commission. He couldn't stop fiddling, exploring new combinations of materials, structural gymnastics, different roof pitches. I never thought much about the planters until I visited some of his Prairie Houses, 2 or 3 weeks ago. Lately they have become something of a passion.

This one from the Heurtley House features a square base, then a cross, and finally a circular bowl. These are the three motifs in the logo he used during his Oak Park period.

My third Point-World planter is from his own house & studio. Built using a loan from Sullivan, this was his base right up to the Robie design: the family home he abandoned when he left Oak Park with Mamma Cheney. The planters are outside the entrance to the studio, itself an addition to the original house.

Louis Sullivan was his mentor and the source of some of his design ideas, particuarly the obsession with ornamental detail which can be a little embarassing to those who like to claim him as a modernist. But perhaps the more important skill he acquired from Sullivan was the ability to harness a team of draughtsman and drive them like a maniac towards his goals.

We idolise the creative artist, but in reality most of them ran studios. From Brunellischi to Gehry, the "great man" produces master-works from an assembly line, often using cheap semi-volunteer labour and almost always claiming the credit (and if you are Steve Jobs, the copyright) This is not to belittle the skill and vision of such men. The draughtsman is always free to set up on his own, perhaps by breaking his contract, as Wright did to Sullivan when he designed his "Bootleg Houses" less than a block from his own house, while serving out the 5 years exclusive service he had contracted in return for the building loan.

There are many more Wrightian planters. Please feel free to send me examples. Here are a few.

Winslow House was the first of the houses Wright designed after breaking with Sullivan. The house itself could almost have been by Sullivan, and the planter is conventionally classical. From here on the urns become more abstracted and geometric.

But what can Vanilla do ? (the challenge in my title) Can we achieve the same scalability using standard Family Editor geometry ? I chose the Nathan G Moore house.

The planter may date from the renovation that followed a fire more than 20 years after the original design. Difficult to be sure. The house itself is rather fussy and steep-pitched, not at all typical of his mature prairie style, whereas the planter is somewhat simpler.

Whereas Point World relies on the Normalised Curve Parameter (NCP) for much of its scalability, Vanilla prefers Reference Planes and equalisation constraints.

The formulae for isolating "Height" and "Slenderness" as the 2 primary user inputs are common to both methods however.

I didn't attempt a "Depth Factor" in Vanilla. Firstly I don't think it can be done. Secondly it's questionable how useful it is in this particular case. To be honest the oval/oblong versions of the planter look a little odd.

So what's the verdict? I enjoyed pitting the two worlds against each other on a similar task. I think the Point-World approach to scaling is more elegant, but Vanilla families are more servicable at present for use in real projects.

I had to cheat a little to get the various segments defining my vanilla revolve to snap to grid intersections. The NCP approach makes small adjustments much easier to achieve. Equalised dimensions are a little crude in comparison. I ought to mention that the Vanilla method makes use of the ability of splines to scale proportionately when their two ends are stretched apart.

All in all, I don't think there's a clear winner: just 2 different methods for making stuff that are worth practising and perfecting. Sometimes one will suit your needs better, sometimes the other. Point World can make shapes that are impossible with Vanilla. Point World only exsists (at present) in family templates that are not ideally suited to objects like planters, furniture, or plumbing fixtures.

So "viva la difference" and keep playing with both methods. Hope you found this useful. And if you are a Frank Lloyd Wright fan, please don't take offence. He was a lovable rogue, by all accounts and I prefer to love him "warts and all" rather than worship at the feet of my idol.