The first thing I did when I got to St Louis for #BILTNA was to take a stroll down town to see the Wainwright Building. In the flesh, the balance between plain surfaces and luxuriant terracotta reliefs is quite impressive.

I will have more to say about this building in a future post. For now the focus is on terracotta as a building material, and how best to represent these kinds of elements in Revit. It's an LOD issue and I don't think we have a truly definitive answer at this point in time.

But Paul Aubin posted an interesting contribution to the debate at the end of the conference.

https://recap360.autodesk.com/project/0f4c83feb3894f64b2a5ad3b646ee15c

His session had been about Reality Capture, a topic which embraces a number of techniques for digitising 3 dimensional objects. He used photogrammetry in this case and displayed the results in the Recap cloud. I responded to his tweet with a suggestion to process the mesh in 3d Max, hiding edges and feeding the results into a line-based family...

Which he did in the blink of an eye, and shared the family so I could also play around with it.

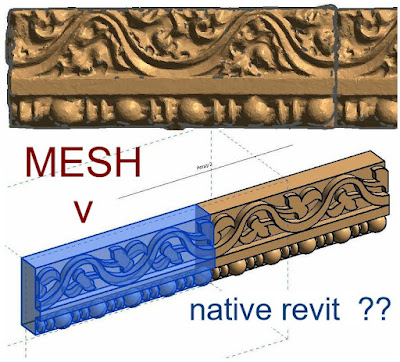

This technique evokes the texture of the original terracotta cladding material very successfully when presented in realistic views. It's also OK in shaded views, and even hidden line with shadows turned on. But without shadows the decorative motif doesn't pick up at all in traditional building elevations (line drawings) You would have to add detail lines to the family and manager their visibility carfully.

I decided to make a native Revit version for comparison. The result is very crisp and impressive in hidden line elevations, but doesn't really evoke the particular texture of well crafted terracotta. I'm not advocating either approach as universally superior. You need to think about what you are trying to achieve: who is using the model. and for what purposes?

In my mind, this is an important debate, very relevant to my ongoing attempts to model classical elements in a BIM friendly way. A similar discussion crops up when thinking about the role of Art in the modern world.

"Abstraction" and "Representation" : are they opposite poles of a spectrum? or are they just two sides of the same coin: necessarily present in any process of exploring reality and meaning?

The terracotta element that Paul captured was part of the amazing displays at the City Museum which was opened up to the BiLT delegates on Thursday Night. It's more of a cross between an art exhibit and an adventure playground than a traditional museum, but full of fascinating salvaged bits and pieces. George Elmslie was responsible for much of the terracotta that enlivened Sullivan's buildings. Examples of his work were piled up in great heaps and interspersed with his delicate pencil design sketches.

https://www.citymuseum.org/

I can't help feeling that we have lost something magical. Imagine skilled artisans using those pencil sketches to guide their muscular fingers and thumbs as they shaped wet clay into flowing foliage. With Sullivan in the background judging the balance between bold massing and expressive detail.

Last night I started to sketch over another image from the museum. It's an interesting challenge to translate these convoluted forms into flat extrusions, and it may well be the key to creating placeholder objects within a BIM model.

Surely the wild, twisting forms were a rebellion against the ordered formalism of classicism. There is a refusal to submit to mechanical order, a revelling in the fluid ambiguities of wet clay, a return to the primitive entanglements of celtic art. History tells us that mechanical purity won out. Art Nouveau and Expressionism ran out of steam in a way that abstraction and minimalism never have. But still there is an emptiness in the mechanical solution that so often leads us back to the trap of nostalgia.

Maybe there was something to be said to the measured tones of a classical language after all. I can't help feeling that the charm of the Wainwright Building lies in the fact that, although it flirts with wild, decorative excess while embracing new, disruptive technologies that presaged the skyscraper age; it actually lies within the classical tradition. Essentially it is a highly abstracted Corinthian column, complete with plinth, fluted shaft, and luxuriant capital.

I will have more to say about this building in a future post. For now the focus is on terracotta as a building material, and how best to represent these kinds of elements in Revit. It's an LOD issue and I don't think we have a truly definitive answer at this point in time.

But Paul Aubin posted an interesting contribution to the debate at the end of the conference.

https://recap360.autodesk.com/project/0f4c83feb3894f64b2a5ad3b646ee15c

His session had been about Reality Capture, a topic which embraces a number of techniques for digitising 3 dimensional objects. He used photogrammetry in this case and displayed the results in the Recap cloud. I responded to his tweet with a suggestion to process the mesh in 3d Max, hiding edges and feeding the results into a line-based family...

Which he did in the blink of an eye, and shared the family so I could also play around with it.

This technique evokes the texture of the original terracotta cladding material very successfully when presented in realistic views. It's also OK in shaded views, and even hidden line with shadows turned on. But without shadows the decorative motif doesn't pick up at all in traditional building elevations (line drawings) You would have to add detail lines to the family and manager their visibility carfully.

I decided to make a native Revit version for comparison. The result is very crisp and impressive in hidden line elevations, but doesn't really evoke the particular texture of well crafted terracotta. I'm not advocating either approach as universally superior. You need to think about what you are trying to achieve: who is using the model. and for what purposes?

In my mind, this is an important debate, very relevant to my ongoing attempts to model classical elements in a BIM friendly way. A similar discussion crops up when thinking about the role of Art in the modern world.

"Abstraction" and "Representation" : are they opposite poles of a spectrum? or are they just two sides of the same coin: necessarily present in any process of exploring reality and meaning?

The terracotta element that Paul captured was part of the amazing displays at the City Museum which was opened up to the BiLT delegates on Thursday Night. It's more of a cross between an art exhibit and an adventure playground than a traditional museum, but full of fascinating salvaged bits and pieces. George Elmslie was responsible for much of the terracotta that enlivened Sullivan's buildings. Examples of his work were piled up in great heaps and interspersed with his delicate pencil design sketches.

https://www.citymuseum.org/

I can't help feeling that we have lost something magical. Imagine skilled artisans using those pencil sketches to guide their muscular fingers and thumbs as they shaped wet clay into flowing foliage. With Sullivan in the background judging the balance between bold massing and expressive detail.

Last night I started to sketch over another image from the museum. It's an interesting challenge to translate these convoluted forms into flat extrusions, and it may well be the key to creating placeholder objects within a BIM model.

Surely the wild, twisting forms were a rebellion against the ordered formalism of classicism. There is a refusal to submit to mechanical order, a revelling in the fluid ambiguities of wet clay, a return to the primitive entanglements of celtic art. History tells us that mechanical purity won out. Art Nouveau and Expressionism ran out of steam in a way that abstraction and minimalism never have. But still there is an emptiness in the mechanical solution that so often leads us back to the trap of nostalgia.

Maybe there was something to be said to the measured tones of a classical language after all. I can't help feeling that the charm of the Wainwright Building lies in the fact that, although it flirts with wild, decorative excess while embracing new, disruptive technologies that presaged the skyscraper age; it actually lies within the classical tradition. Essentially it is a highly abstracted Corinthian column, complete with plinth, fluted shaft, and luxuriant capital.

The closing keynote

at BiLT featured Sabin Howard talking about maintaining the human touch while

using cutting edge technology to support the production of monumental

sculpture. It's a challenge that resonates with me and echoes through the pages

of this blog at regular intervals.

BIM is fantastic, but let's not forget the thousands of years of drawing by hand that preceded it. The human touch is vital.

BIM is fantastic, but let's not forget the thousands of years of drawing by hand that preceded it. The human touch is vital.

A lutta continua.

The struggle continues.