Four weeks ago I dragged my son Tom around a bunch of John Soane buildings in London, taking photos like a nutter. There are 3 churches, his tomb, the Dulwich Picture Gallery, his house in Lincolns Inn, and of course the Bank of England (what's left of it) I didn't get around to Pitzhanger Manor or the Chelsea Hospital Stables, but I did pick up some books which reference these and other project that are either outside London, have been demolished, or were never built.

All this, inspired by Project Soane. Look it up if you don't know. I'm very excited to be contributing to this initiative which brings into the public realm ideas I have been banging on about for some time now. In particular the belief that the BIM pencil is an amazing tool with applications way beyond what we do in our day jobs: education, research, publications, history of architecture, history of civilisation, lots of stuff that we have been doing with ordinary pencils since before John Soane was born in a village near Reading, son of a bricklayer, destined to rise to dizzy heights in an age of revolutions.

The next weekend was spent in Somerset, with my old schoolboy mates Ian & Al, plus other friends picked up over the ensuing 50 years or so in various parts of the world. The 3 of us went to Barnsley Grammar School back in the ice age, or rather the "swinging sixties" and have had a passion for music ever since. We have a band, affectionately known as the Barnsley Vista Social Club, which meets occasionally and gigs about once a year, basically when I'm in the same hemisphere as the others.

Down in Somerset we stayed at a place with definite sixties connections, pictures of Lulu and Engelbert Humperdink who stayed there when it belonged to a musician of the era. The gig itself was in the village hall just across the road from where Al lives. We had a brilliant audience, many with definite 1960s credentials, who got up and danced when I broke into my Howling Wolf impression. It was a night to remember and we raised a surprising amount of money for Nepal in the process. What a privilege to have shared my youth which such remarkable people.

For the last 2 weekends I have been busy with my BIM pencil, exploring the Bank of England as it was around 1830, when Soane retired, Napoleon was a fading memory and railways were about to burst upon an unsuspecting world.

I decided to start (as I usually do) by getting a sense of scale and an overview of the whole building. Screen grabs from Google Earth and Bing Maps both give similar results. Google Earth has a long scale bar that resizes dynamically as you zoom. Very clever, but perhaps misleading. I don't think we can be so sure about the accuracy of the scaling of imagery that is assembled "automatically" from various aerial sources. Perhaps Bing is a little wiser in just giving us a short bar with a rounded off value.

Fortunately we have a couple of plans that were drawn up by architects that followed Soane. (Cockerell was one) There are also dimensioned drawings for rooms like the Stock Office that has now been lovingly restored as the Bank Museum. So I was able to do a cross-check on the overall scaling. The result is my best guess at a filled region to represent the bank perimeter and the positions of the couryards and light wells that existed when Soane had finished weaving his magic.

I have deliberately set the two main corners at right angles. Almost certainly this is not quite correct. Life never quite lives up to these abstract ideals. I'm sure Plato would have agreed with me. We have no choice but to simplify. There would be no point in trying to record every millimetre of deviation from an ideal plane. The question at hand is "how much to simplify". I have chosen to use right angles wherever possible. Deviating by fractions of a degree is not something Revit likes to do. We would be mad to attempt it.

Taking this discussion a step further, I felt the need for a grid. This helps us to orient ourselves when jumping from plan to section to elevation. I find grids invaluable in helping to minimise human error. Revit has wonderful grid and level tools (best in class springs to mind) Let's make use of them. Feel free to argue otherwise. Now is the time to hammer this out.

I have also chosen to space my grids at round-figure intervals. The position of walls in relation to these grids will be subject to revision as we go along, but let's keep things simple if we can. Perhaps we will decide to rotate one or two walls by a degree or two relative to the grid later on. This may be the only way to make sense of window spacings for example in some of the internal courtyards. But I propose to start by setting all walls parallel to the three sets of grids that I have prefixed with A/B, C/D & E/F (A being at right angles to B, etc)

I would have liked the angle between Princes Street and Lothbury to be 60 degrees (wouldn't we all). Sadly it is not so. I started with 61 but later adjusted this to 61.5 in order to make Tivoli Corner work. It's a mission to rotate whole sections of the grid, so I hope we don't have to do this again, but you never know.

I am also assuming that certain sections of the facades are perfectly symmetrical with well defined mirroring axes. We will get in an awful muddle if we don't do this I think. Clearly that was Soane's intention which is more than good enough for me.

Similary the walls are at present defined in multiples of six inches. Which brings me to the topic of units. Most of the world works in Napoleans units. Despite claiming to be the world's greatest democracy, the US cannot get past the Imperial System that it inherited from its former colonial masters who invented the Bank of England way back in 1694. Soane of course also used this system, despite a certain admiration for Napoleon implied by items in the unbelievable collection of artefacts, paintings and historical relics that he assembled in his house, now the Soane Museum in Lincoln's Inn Fields. Take a visit if you ever get the chance. To say he was obsessed with the classical period and a man of the most remarkable energy and dedication would be a huge understatement. Also his fascination with effects of space and light is brought to life here in a way that words or even pictures could never convey.

At primary school with my mate Ian, I used feet and inches. The metric system came upon us after we joined Alan at BGS if I remember rightly. In my bricklaying days there was an overlap. We measured brickwork in millimetres, but timber sizes still tended to be thought of in terms of 2 by 1, and 6x2. Strangely in the UAE we still measure floor areas in square feet, even though everything else is metres and millimetres. I am struggling a bit with my memory box, but it's fun to work in unfamiliar territory, kind of like playing the blues in A flat perhaps. Unexpected insights.

There is a splendid drawing that was provided on the Project Soane site which has the perimeter wall in plan and elevations arrayed around. Many of these are in pairs showing Soane's "before and after" vision for transforming the work he had inherited from the two previous architects of the Bank. I cut and pasted sections of this as backgrounds for my 4 principal elevations and scaled them up as best as I could. This gave me a basis for deciding on the vertical scaling. After some experimentation I have settled on a figure of 25 feet for the height of the Corinthian Columns and Pilasters that feature all around the perimeter at various points. This may well be wrong, but we have to start somewhere.

The stonework is set in horizontal bands with recessed horizontal joints and flush verticals. Many architects have used this device, Wright for example was very fond of it, witness

Robey House. Using my 25 foot guesstimate, these bands would be spaced at 1' 4". This can be easily checked (I'm embarassed that I didn't think of it when I was there) Maybe I will ask my son Tom to nip down with a tape measure some time.

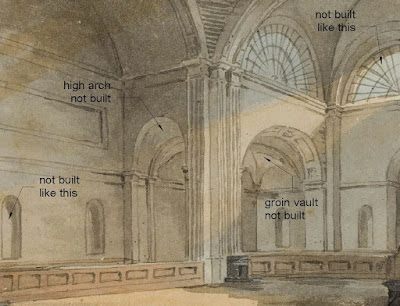

I've done a few of these kinds of studies before. (Ronchamp, Casa del Fascio, Lever House, the Gherkin, Robey House, De la Warr Pavilion ...) You can never nail things down 100%. There are always little anomalies and discrepancies that I fail to resolve completely. Photos say one thing, plans another, elevations and sections something slightly different. The St Bartholomew's Lane elevation in Soanes drawing does not match the plan drawn directly above it. He gives two elevations (before and after) but neither of them match the plan. Clearly he changed his mind about how to modify the frontage he had inherited from Taylor. I am following the plan, which tallies well with a historical photograph taken in the 1920s.

Actually I am giving preference to the plan drawn by Cockerell. This is the one supplied on A360 and used as an underlay in most of the uploaded Revit files. It's not perfect, but it seems to be the best we have. The BIM pencil allows us to coordinate plans, sections and elevations with a precision that was unavailable to Cockerell, so I've made minor adjustments here and there. Bear in mind also that even if he did become aware of discrepancies half way through the drawing process he would most likely have faked some of the dimensions rather than start the drawing again from scratch. That was the reality we faced when we worked entirely by hand. You took more care to get things right first time, but at some point in the process you were forced to accept the small errors that had crept into a set of drawings that might represent hundreds of person hours.

In the spirit of crowd-sauce I wasn't going to make the blind windows from scratch. I had been using a simple rectangular recess, good for starters, maybe I will go back to that later on and represent the bank as a very simplified abstraction to show what we have learnt about the composition. Some good work in the family I downloaded, but I needed to adjust the proportions to suit my assumptions. Don't know for sure who's right on this, but I need to follow through consistently with the line I've taken. Also the head and sill were not quite right on closer inspection. So I gave them a bit more depth. I'll come back to this again later perhaps (or someone else will grab the baton) but for now it does the job.

Another week has gone by since I started this post, so I need to wind it up. My last image will be based on two photos I took at the Dulwich Picture Gallery on a beautiful sunny day at the beginning of August.

I think it's not too far-fetched to say that the red telephone box is a precursor to wi-fi spots, which is not to say that John Soane invented the internet, but there is a connection and it has to do with style. Style matters to humans. It mattered to our ancestors a million years ago when they made symmetrical flint axes and it matters to those who purchase apple's exquisite digital toys.

Monuments use style to convey respect for past events and personalities. Soane had a thing about shallow domes with segmental pediments. Giles Gilbert Scott re-purposed this stylistic motif to add dignity to the democratisation of telephony, which brings us back to the public telephone box: access to global communications for the man in the street, just like today's smart phones.

Important questions. What was Soanes "style" all about? How do we capture the essence of that style in a BIM model? Why are we doing this in BIM (as opposed to visualisation software)? What is the most appropriate level of abstraction/simplification? Can we find a flexible approach to LOD ? (strategies for switching between levels of abstraction, swapping out components etc) What is the balance between product and process? Showing off v learning? Visualisation v Historical Analysis? Recording the past v exploring interpretations.

More to come, day job permitting.

For those who don't have access to Project Soane, and/or Revit 2016 here's a link to a PDF of my work so far.

Bank of England.pdf